When four new SI prefixes were added to the International System of Units (SI) in November 2022, one of the main reasons cited for their need was for their use in data science, where the numbers involved in describing quantities of information have become ever larger. e.g. The amount of data generated by the internet is projected to hit 175 zettabytes by 2025.

It was noted that unofficial prefixes, such as “hella” and “bronto”, were already being improvised for multiples in excess of 1024, and that there was a danger that if the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) did not prescribe official SI prefixes for such large multiples, confusion could soon follow with one or more unofficial prefixes becoming de facto standards.

It is notable that information units such as the bit, and bit per second, are not included in the SI, but the use of SI prefixes with such units has nevertheless provided the impetus for the introduction of new SI prefixes at this time.

Indeed, in everyday use, most people probably only ever come across SI prefixes for large multiples, such as “mega”, “giga” and “tera”, in the context of computer data storage capacities, and internet broadband speeds.

Binary prefixes

In the early years of digital computers, a need developed for a way to describe larger and larger multiples of bits and bytes.

In binary computers, it is often most convenient to handle data in multiples of powers of two. However, it was noted that 210, or 1024, is similar in size to 103, or 1000, and so a convenient solution was to adopt the use of SI prefixes, such as “kilo” and “mega”, for computer technology, but to use these prefixes to describe multiples of powers of two, rather than the standard multiples of powers of 10 defined in the SI.

This is of course strictly not in accordance with the SI. The SI Brochure, the official rules for the use of metric units, says the following about the use of prefixes with information units:

The SI prefixes refer strictly to powers of 10. They should not be used to indicate powers of 2 (for example, one kilobit represents 1000 bits and not 1024 bits).

Needless to say, this dual use of prefixes to mean different amounts has been a source of confusion in the field of information technology ever since.

To bring an end to the confusion, a set of non-SI binary prefixes was introduced by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) in 1999. In 2009, these binary prefixes were included in ISO 80000-1. These binary prefixes are for use with information units only and should not be used with SI units.

This means that there is no longer any excuse to use SI prefixes for multiples other than their standard SI values.

The table below shows the official IEC binary prefixes, together with the two new binary prefixes, “robi” and “quebi” (which have yet to be published by the IEC).

| Prefix | Symbol | Value | |

| quebi | Qi | 2100 | 102410 |

| robi | Ri | 290 | 10249 |

| yobi | Yi | 280 | 10248 |

| zebi | Zi | 270 | 10247 |

| exbi | Ei | 260 | 10246 |

| pebi | Pi | 250 | 10245 |

| tebi | Ti | 240 | 10244 |

| gibi | Gi | 230 | 10243 |

| mebi | Mi | 220 | 10242 |

| kibi | Ki | 210 | 10241 |

The introduction of binary prefixes is a welcome development as they help ensure that SI prefixes are universally understood in whatever field they are used.

Confusion caused by incorrect use of SI prefixes

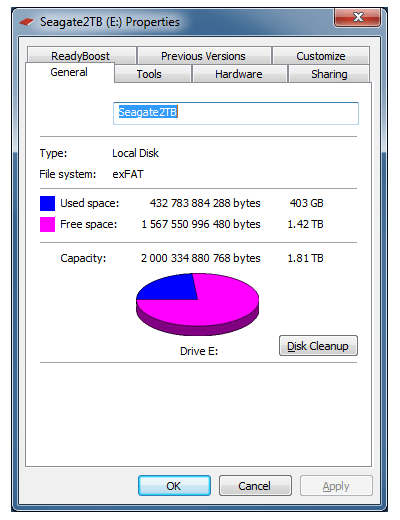

The most obvious example of the confusion caused by the incorrect use of SI prefixes is with hard drives. Hard drives are generally marketed using SI prefixes correctly, in terms of gigabytes or terabytes. However, some operating systems still show disk capacity and usage using SI prefixes incorrectly, leading some consumers to feel that they have been misled.

|

|

e.g. The Seagate One Touch, 2 TB, Portable External Hard Drive has a capacity of 2 000 334 880 768 bytes (approx. 2 terabytes, or 2 TB), which equates to approx 1.81 tebibytes, or 1.81 TiB.

However on a PC running Windows, the capacity and disk usage is shown in terms of gibibytes or tebibytes, but the corresponding symbols shown are those for gigabyte and terabyte.

A disk capacity of 1.81 TB would equate to 1.65 TiB.

Further reading

Binary prefixes

https://metricsystem.net/prefixes/#binary

NPL leads expansion to the SI prefix range for the global metrology community

https://www.npl.co.uk/si-prefix

Earth now weighs six ronnagrams: New metric prefixes voted in

https://phys.org/news/2022-11-earth-ronnagrams-metric-prefixes-voted.html

Prefixes for binary multiples

https://www.iec.ch/prefixes-binary-multiples

IEC 60060

https://www.electropedia.org/iev/iev.nsf/IEVref_xref/en:112-01-27

SI Brochure: The International System of Units (SI) – updated 2022

https://www.bipm.org/en/publications/si-brochure

Also defined in IEEE Std. 1541, initial edition 2002, current edition 2021.

LikeLike

As always with these things it comes down to industry usage.

I and the wider Linux community have been routinely using GiB and TiB for years. I just noticed they are no longer flagged as errors, so things are moving on.

Unfortunately the wider industry refuses to use these prefixes, a bit like the KPH used by the American AP style guide which few can afford to ignore.

Of course we also know the ensuing confusion is what sells GB rather than GiB hard drives and few know the difference.

Now if only we could get rid of those meaningless and awful ‘short’ American billions an trillions.

LikeLike

A couple of simple questions about laptops, phones, etc. currently storage, memory, broadband speeds etc. is given in for example Mb.

*When will Broadband providers start to use these official units? Will it be within the next few years, or will we need to wait decades?

*When will devices like laptops, being sold online and in stores such as PC World/Currys have this official correct info shown on them? Guess, place your bets, – I’ve no idea!

LikeLike

The common assumption that the decimal prefix “k” can be used where the binary prefix “ki” should be used is based on the premise that 10^3 is very close to 2^10 (1000 vs 1024 – a 2.4% difference). However, as numbers increase the proportional difference also increases and 2^100 is 24% larger than 10^30, not 2.4%.

LikeLike

The common assumption that the decimal prefix “k” can be used where the binary prefix “ki” should be used is based on the premise that 10^3 is very close to 2^10 (1000 vs 1024 – a 2.4% difference). However, as numbers increase the proportional difference increases more rapidly and 2^100 is 24% larger than 10^30 rather than 2.4%.

LikeLike

Another point is the difference between ‘bits’ (b) and Bytes (B), a factor of 8x difference and often wrongly used.

A simple everyday example of correct usage of b and B: –

ISP: xxxxxx

Latency: 7.85 ms (0.34 ms jitter)

Download: 71.36 Mbps (data used: 33.9 MB)

Upload: 17.35 Mbps (data used: 7.8 MB)Packet Loss: 0.0%Result URL:

Also disk usage: – 489.1 GiB (525,193,455,691) 297 files, 34 sub-folders.

So 525.2 GB is only 489.1 GiB, the real figure.

As for when they will ever be correctly used, certainly not in most of our lifetimes, try asking consumer sites, they are the ones that should be addressing this issue. Not for the faint hearted though.

LikeLike

I’ve worked in the IT industry for many years, right from the early days of PCs to the present day. I can count in my head powers of two up to around 2^14 and instinctively know that anything with ‘TB’ should mean 2^40 or 1024^4, not 10^12 !

However, disk and memory manufacturers produce and market in capacities based on powers of 10. For example, the SSD disk in my laptop is marked as 240 GB and if I interrogate the actual size (I use PowerShell commands but there are alternatives) it returns 223.56 GiB (Bytes x 1024^4). This equates to 240 GB (bytes x 10^12). So, technically, the GB/TB suffixes they use are legally correct.

Unfortunately these MB/GB/TB suffixes for memory or disk capacities have just become ingrained in the industry, similar to the way that TV screen sizes are almost always shown in (decimal) inches. Personally, I always feel I’m being cheated by the manufacturers taking a big bite out of the bytes I had expected!

LikeLike

Modernman,

If the “industry” is using the SI prefixes to mean anything other than 10^X, then they are wrong, no matter how ingrained the practice is. Doing so degrades the consistency and coherency of SI thus removing SI from technically be called a system.

Lucky for us, the BIPM and CGPM don’t condone the misuse of the prefixes and SI is safe from those who abuse and misuse SI rules. The “industry” needs to correct their error and stop pushing out incorrect prefix usage, especially when one part of the industry is using the SI prefixes correctly and others are not. What would it take to force a clean-up?

If I’m not mistaken floppy disks were once described in a hybrid fashion, where a “megabyte” meant a kibibyte times a kilobyte. I know floppy disks are obsolete and no longer produced, but I hope this insane practice isn’t still going on. I hope a gigabyte hard drive isn’t a kibibyte time a kilobyte times a kilobyte.

The fix should be simple. Computer operating systems like Windows can easily provide a software update to show disk space, etc using the right prefixes. They can even have both if the wished. but not use either incorrectly or mixed together.

LikeLike

This post is about prefixes, just not the binary ones.

Here in the USA most people outside of work that requires it have no clue how to use the metric system. A very clear example is with medicines or supplements that typically list a dose of 1 gram as 1000 milligrams. This is because Americans don’t understand prefixes and treat “milligram” as a fixed undecomposable unit.

Of course, even in metric countries folks do with with “kilometer”. So, they might say “1,000 kilometers” instead of “1 megameter”. That’s a tough nut to crack, apparently.

I’m just curious if most folks in the UK understand prefixes better than we do here in the USA. I do hope so!

Cheers, Ezra aka punditgi

LikeLike

Ezra:

In the UK road signs are still in miles. There are no prefixes for very large numbers of this unit, so we routinely hear hundreds, thousands, millions of miles in, for example, reports about distances in space. By analogy, those distances are reported as hundreds, thousands and millions of kilometres too if metric is being used. Ditto for very large numbers of litres. Until the metric system is firmly embedded and in use in the UK and the USA, I don’t think there’s much chance, outside of the scientific world, of the full range of prefixes being used. I’m speaking as a non-scientist, but that’s how I see it. Perhaps a scientist will correct me.

LikeLike

My experience is that most Brits understand the concept of prefixes, though many get confused between the prefices “mill-” and “centi-“. I recall a few years ago getting off the “Waterloo and City” shuttle at the “City” end on my way to the office. A group of three office workers (male) were discussing which was the bigger, a millimeter or a centimeter.

I have had similar problems with the odd 17-year old student when I was giving extra physics lessons. I knwe that she had been to France on a number of occasions, so I asked her what money she used. She replied “Dad paid for everything”. Whe my wife and I went abroad with our children , we gave them their p[ocket money in the local currency at the “mum-and-dad exchange ratge” (which way always whole numbers – 3 D-marks to the pound etc). Once most of the EU had switched to the euro, they knew that thre were 100 cents in a euro from which it followed that there were 100 centimetres in a metre.

LikeLike