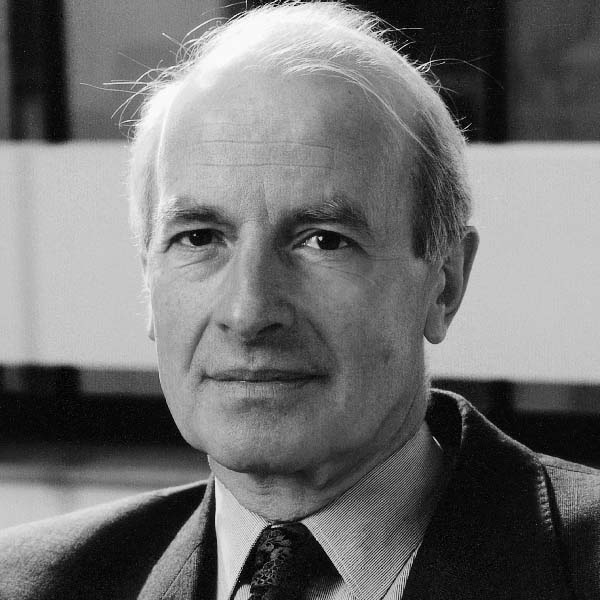

We at UKMA are deeply saddened to learn of the death of UKMA’s longest-serving patron, Dick Taverne, Baron Taverne of Pimlico. He was a man with a stellar career both in politics and outside, and was an avid supporter of UKMA and its cause.

Those of us who are old enough will remember when he rose to national prominence in 1973 by parting company with the Labour party, in which he had been a minister, and successfully standing in his Lincoln constituency against a Labour candidate. In the words of the Guardian, “Nothing quite like it has been seen this century in British elections. Mr Taverne must earn the title of Dick the Giant Killer.” That is of course a sign of the times – since then quite a few others, not least a former party leader – have followed suit.

That remains one of his claims to fame. However his distinctions go way beyond that. Indeed he was a man of extraordinary enterprise, achievement and innovation, a strong internationalist and many would say a true Renaissance man.

He was born in 1928 in Sumatra, then part of the Dutch East Indies, where his father worked for Royal Dutch Shell. He started life as a Dutch national, as were both his parents. Moving to the UK at the outbreak of war in 1939, before Indonesia was occupied by the Japanese, he attended Charterhouse School. He was naturalised as British at the age of 21. He gained a First in Greats/Classics at Balliol College, Oxford. At the Oxford Union he was an active debater, and almost became president of the Oxford Union, being beaten by his contemporary Jeremy Thorpe. In 1951 he toured America on a debating tour, accompanied by William Rees-Mogg (yes, the future Times editor and father of Jacob). He made a move into the legal profession, and was called to the Bar in 1954, becoming a QC in 1965.

Despite coming from a Conservative family, he developed an affiliation with Labour early in life, and chaired the Oxford University Labour club, where he was talent-spotted.

Dick’s first sortie into parliament was unsuccessful, in Putney in 1959. However, in 1962, he was hand-picked by party leader Hugh Gaitskell to contest the Lincoln seat for Labour, and he won, remaining a Labour MP for 10 years. He experienced some conflict with the left-wing faction of his constituency party, who described him as “middle class, legalistic and academic”. A bone of contention was his strongly pro-European views and his support for entry into the then-EEC. During his years in parliament, he was a Minister in the Home Office in the Wilson government from 1966 to 1968, a Minister of State in the Treasury (1968-69), then Financial Secretary there from 1969 to 1970, in the run-up to decimalisation. Finally he was Chair of the Public Expenditure (General) Sub-Committee from 1971 to 1972.

In 1971 he followed Roy Jenkins in a rebellion against the party’s policy of remaining outside the EEC. As he put it, “When the future of one’s country is at stake one doesn’t sit on the fence.”

Eventually local conflict led to his de-selection by the Lincoln party – a decision supported by his former friend Tony Benn. He not only resigned as a Labour MP, but created a by-election, standing as a Democratic Labour candidate. He recaptured the seat – with almost 60% of the vote – and held it through one general election, representing Lincoln as MP from March 1973 to September 1974. He eventually lost his seat to future senior Labour cabinet minister, Margaret Beckett. It has been said that his victory opened the door to the split in Labour which led to the establishment of the SDP. He was an early member of that party and joined its National Committee. Following the party’s merger with the Liberals, he became a founder member of the Liberal Democrats, whom he later represented in the Lords following his elevation to a life peerage in 1996.

He reflected on his experiences in Lincoln in the book The Future of the Left:Lincoln and After (1974).

Although finance was in effect his third career, after classics and the law, he put his expertise in that area to good use. In 1970 he launched the Institute for Fiscal Studies, of which he was the first director, and later chair. The institute continues to thrive, to this very day. He also became chair of the think tank, the Public Policy Centre.

Dick had a lifelong interest in science – perhaps his fourth career – and in rational decision making – not surprising for a patron of our Association. In 2002, he founded Sense About Science, a charity to promote the an evidence-based approach to scientific issues. He authored The March of Unreason (OUP) in 2005. His main interest remained science and society. He was elected President of the Research Defence Society in 2004. He was a member of the House of Lords Committee on the Use of Animals in Scientific Procedures, and was a member of its Science and Technology Committee. He won the Science Writers’ Award as Parliamentary Science Communicator of the Year 2005.

Dick was a committed (but in his own words “pragmatic”) environmentalist and, together with his wife Janice, a biologist, he gave up the car and took to cycling around London. However in his writings he argued strongly for reason over dogma in the defence of the environment.

He was an Honorary Associate of the National Secular Society and a supporter of Humanists UK, as well as a vice-chair of the All Party Parliamentary Humanist Group.

Dick became a patron of UKMA in 2003. He worked to identify and amend relevant legislation coming before Parliament in a way that reflects UKMA’s aims. In 2014, he brought forward an amendment to the Consumer Rights Bill, which led to stricter regulation of units of measurement in advertising.

Dick is survived by his widow Janice (née Hennessy) and his daughters Suzanna and Caroline. Our thoughts are with them.

In the words of Andrew Copson, “His legacy lies not only in the causes he advanced but the manner in which he did so: calm, rigorous, and humane. He showed how a humanist outlook can anchor an ethical and courageous public life”.

And, as his party leader, Sir Ed Davey, put it, “Dick was a passionate, principled and thoughtful colleague who will be sorely missed by all of us in the Liberal Democrat family. A founding member of our party, Dick was a passionate European who inspired us all with his sharp intelligence and incredible experience in government, politics and beyond over many decades.”

Further reading

Dick Taverne on Wikipedia

The Guardian – obituary

Sense about Science – obituary

When the young Dick Taverne arrived in the United Kingdom from the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) in 1939, aged 11 he had to get used to many changes. Gone was the tropical weather and probably the lifestyle (Europeans in Indonesia had a similar lifestyle to that enjoyed by Europeans in India). He would have had to complete one more year of primary school before making his choices at the age of 12 regarding what type of secondary education he would be following (Europeans in the Duch East Indies followed the Dutch curriculum). In addition to Dutch, he might have possibly have learnt some English and some Malay (the lingua franca of the Dutch East Indies).

In the “rekenkunde” class he had almost certainly learnt the basics of the metric system – 100 centimetres in a metre, 1000 grams in a kilogram etc. He might also have heard his mother speaking of an “ons” when she was cooking or a “pond” when she was weighing herself. He might have been aware that an “ons” was 100 grams and a “pond” was 500 grams, so even a boy of 11 could deduce that there were 5 “onsen” in one “pond” and if you wanted t convert “ponden” to kilograms, you halved the number.

He was now confronted with not only having all his school lessons in English, but also he had to get his head around the fact that there were 16 ounces in a pound, not 5. Also, there were 12 inches in a foot, 3 feet in a yard and so on. Where were the simple prefixes like “centi” and “kilo”? He must have found some solace in the science class where centimetres and grams were being introduced to the class. At least he understood those (unlike the English schoolboys). It is little wonder then that he supported the metric system.

LikeLike